The tipping point

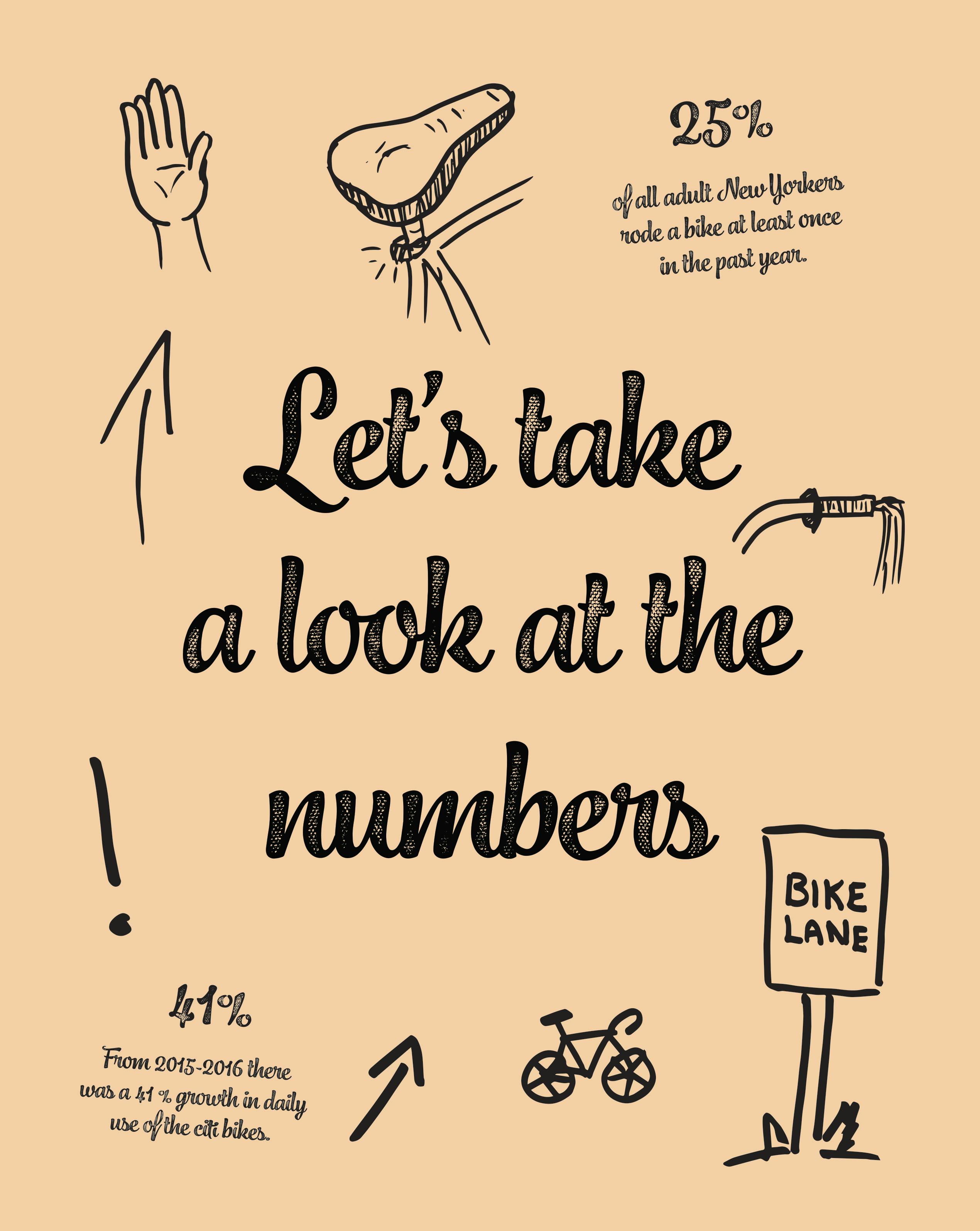

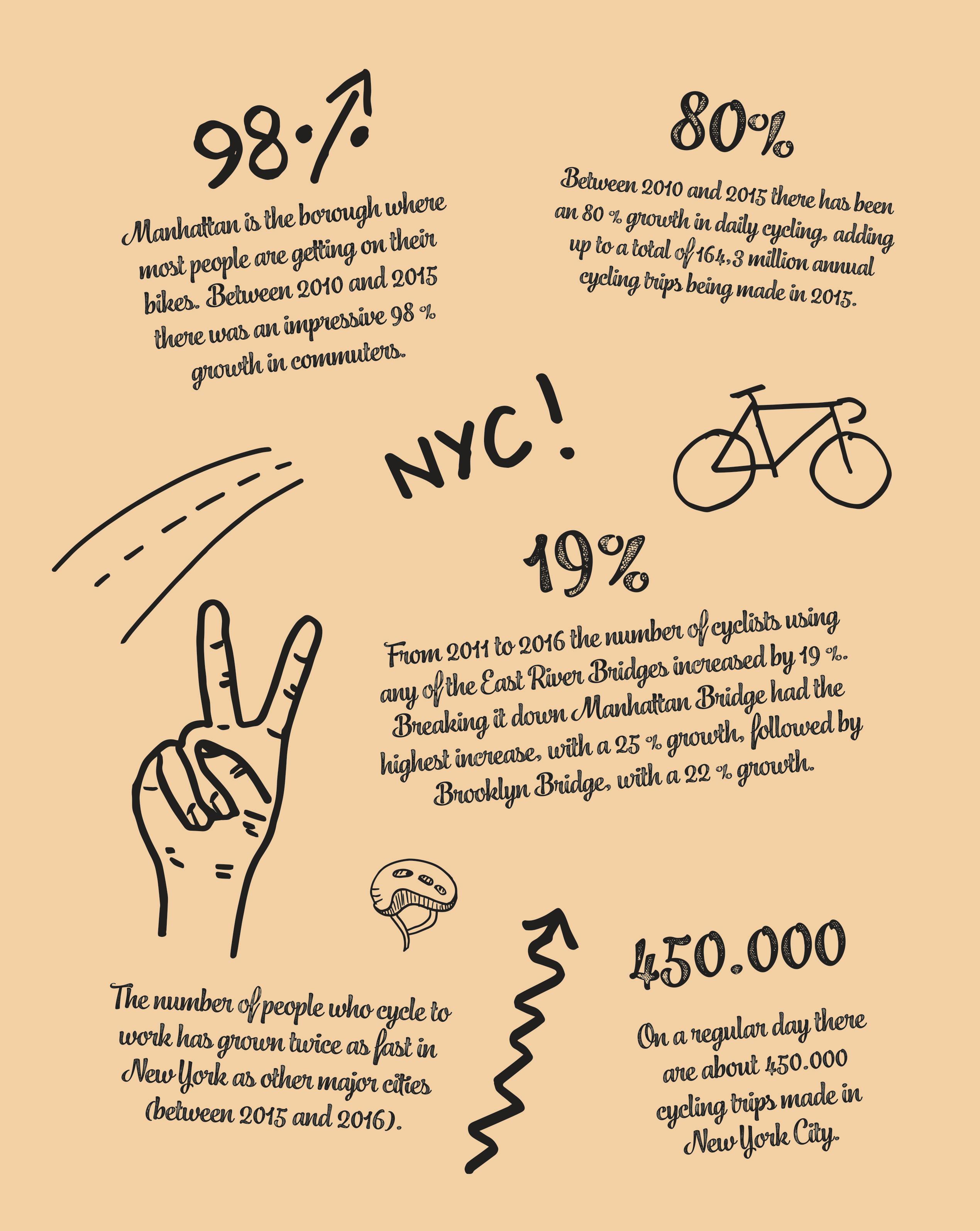

New York City has undergone a rapid transformation over the past decade, building almost 650 kilometres of new bike lanes, quadrupling ridership and creating a bike-share system with over 14 million trips per year.

Text: Pete Dawson

Photos: Mari Oshaug

Janette Sadik-Khan, the City’s former Transport Commissioner, is widely regarded as the chief architect of this bike revolution. Following in the footsteps of visionary urbanists like Jane Jacobs and Jan Gehl, she set about creating a city for people rather than cars.

We are approaching a tipping point for urban mobility, with 70% of the world’s population expected to live in cities by 2050 alongside over 2.5 billion vehicles. The former Mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoe, put it best when he said “cars no longer have a place in the big cities of our time.” Sadik-Khan took this challenge head on, moving quickly to redefine New York City’s streets as public spaces. Her approach challenged the status quo and tore up the outdated traffic models used by city planners and road engineers for decades. While New York City’s cycling network is far from perfect, they built more bike lanes in 10 years than Copenhagen did in 50 years.

It was a hard-fought battle, with Sadik- Khan facing passionate opposition from residents and lobby groups who had grown accustomed to car-centric planning. The unofficial frontline in the City’s fight for street space was a new bike lane along Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. The Brooklyn Paper described it as “the most controversial slab of cement outside the Gaza Strip”. By late-2010, the bike lane was front page news, police were called in to control duelling protesters, supporters delivered thousands of letters on the steps of City Hall and Sadik-Khan’s opponents mounted legal challenges. Of course, the bike lane worked, reducing speeding by 75%, injuries by 63% and tripling the number of cyclists with no impact on traffic flow or travel times. Today, the bike lane is just another part of the streetscape and the majority of residents support it.

New York City has become a much safer place to ride in, with the increased investment in bicycle infrastructure saving more than 1000 lives. The installation of bike lanes on Queens Boulevard, long known as ‘The Boulevard of Death’, almost halved the number of cyclist and pedestrian injuries. Safer streets are good for business too, with pedestrians and cyclists known to make more frequent visits to retail precincts than drivers. When New York City added parkingprotected bike lanes to Ninth Avenue, they saw retail sales in local shops increase by 49%. It’s easy to find a restaurant owner or shopkeeper who believes that bike lanes will hurt their bottom line, but data and experience prove otherwise.

The key to Sadik-Khan’s success was a DIY approach to city making called tactical urbanism, using quick, cheap and scalable interventions to inspire long-term change. In 2009, she controversially closed Time Square to cars with nothing but large orange barrels and 400 folding beach chairs, proving you don’t need a million-dollar budget to remake cities for people. The pedestrianised area has since become a permanent symbol of New York City’s transformation, and is used as an example worldwide to rebut claims that removing cars from cities destroys their urban character. If the most iconic and busy intersection in the world can go car-free, then anywhere can.

In her book, Streetfight: Handbook For An Urban Revolution, Sadik-Khan reflects on Jane Jacob’s fight to save SoHo and Little Italy from the Lower Manhattan Expressway half a century earlier. She laments the urban decay of New York City in the years that followed, arguing that “Jane’s vision of dense, vibrant, inviting and changeable public spaces remained unfulfilled.” The future looks much brighter though, with a growing list of cities around the world restricting car use and building bike lanes to create a better urban environment. Sadik-Khan says “City dwellers around the world are beginning to see the potential of their city streets and want to reclaim them.” The battle for street space is far from over, but the experience in New York City suggests that citizens will prevail.