Alex Singer Cycles

The storefront of Alex Singer Cycles is an institution on rue Victor Hugo in Levallois-Perret in north-west Paris. The same building has borne the name for 80 years but you get the feeling that, on this busy street, backing onto to a major railway hub and surrounded by huge building projects growing into the sky, it is the only piece of continuity, a link to the past.

Text: Nick Chapman

Photos: Andy Donohoe

The business was opened by Alex Singer in 1938, 15 years after he arrived in France from his native Hungary. He had already established himself as a rider on the Paris cycling scene taking part in the Cercle Sportif International as a soloist, and racing and touring in the Tandémistes Parisiens cycling club with his wife Maria, riding across France and most of Europe. Singer perfected his craft working for manufacturer Bianco, and immediately specialised in building touring and tandem bikes, making a name for himself by entering technical competitions well known for showcasing the latest innovations and driving technical progression in bicycle manufacture.

In 1944 Singer apprenticed his young grandnephews, Roland and Ernest Czuka, into the shop, and they soon proved themselves to be proficient and skilled bike-builders. Grafting in the workshop all week, they then rode all weekend with the ‘Cyclotourist Amicale of the Western Suburbs’, the club that Singer set up to be associated with the shop. However other technological advances threatened the business: the moped and affordable car made the future uncertain. Roland came and went, working for Citroën when not building bikes, whilst Ernest kept things going. With his health failing, Alex Singer sold the business to Ernest Czuka in 1965. As the popularity of cycling surged and waned Ernest kept battling on, and was helped out by his son Olivier.

Just as Ernest took the reigns from Alex, Olivier came to the fore as his father grew older, determined to keep the family legacy alive. In 2014 Alex Singer Cycles was designated a French Living Heritage Company in recognition of the institution it has become and the part it plays in French cycling history. BikeVibe had to visit, so we made an appointment.

Olivier Czuka is distant, almost stand-offish, when we arrive at the shop. It is lunchtime, the shop is closed, empty, hushed, museum-like. Although the frontage on the street has been updated, the interior has resisted the advancement of time. The shop is neat and tidy, the original mosaic-tiled floor is spotless, an unassuming wood-panelled counter has a couple of posters tacked to it advertising the next club ride, and on it is the hand-cranked cashiers register that has stood there as long as the shop has been open.

The only apparent concession to modernism is the electronic till sat next to the original – apparently it couldn’t cope with the introduction of the euro.

To the right of the of the counter is a gleaming display of polished steel and chrome where a range of impeccable complete Singer bicycles are lined up. They are beautiful machines, unadorned by paintwork the craftsmanship is obvious with clean lug work and minimal decoration – a simple Alex Singer badge on the steerer and seat post tubes. Czuka is dismissive when I try to draw him with admiration of the elegant aesthetic with a shrug of the shoulders saying, “Of course.” “But,” he says, “They are fast, not just beautiful.”

Closer inspection shows the details that back this up – some of these vintage-looking bikes, complete with leather studded saddles and wide, drop handlebars wrapped with ribbon tape, are fitted out with top of the range modern components: Dura-Ace groupsets and Campagnolo racing wheels.

“You don’t need carbon,” asserts Czuka, “Steel is just as fast. It’s not about the frame but the moving parts.” He tells a story of beating young guys at local races who scoff at his steel steed on the start line but cannot hold his wheel when he sprints for the line.

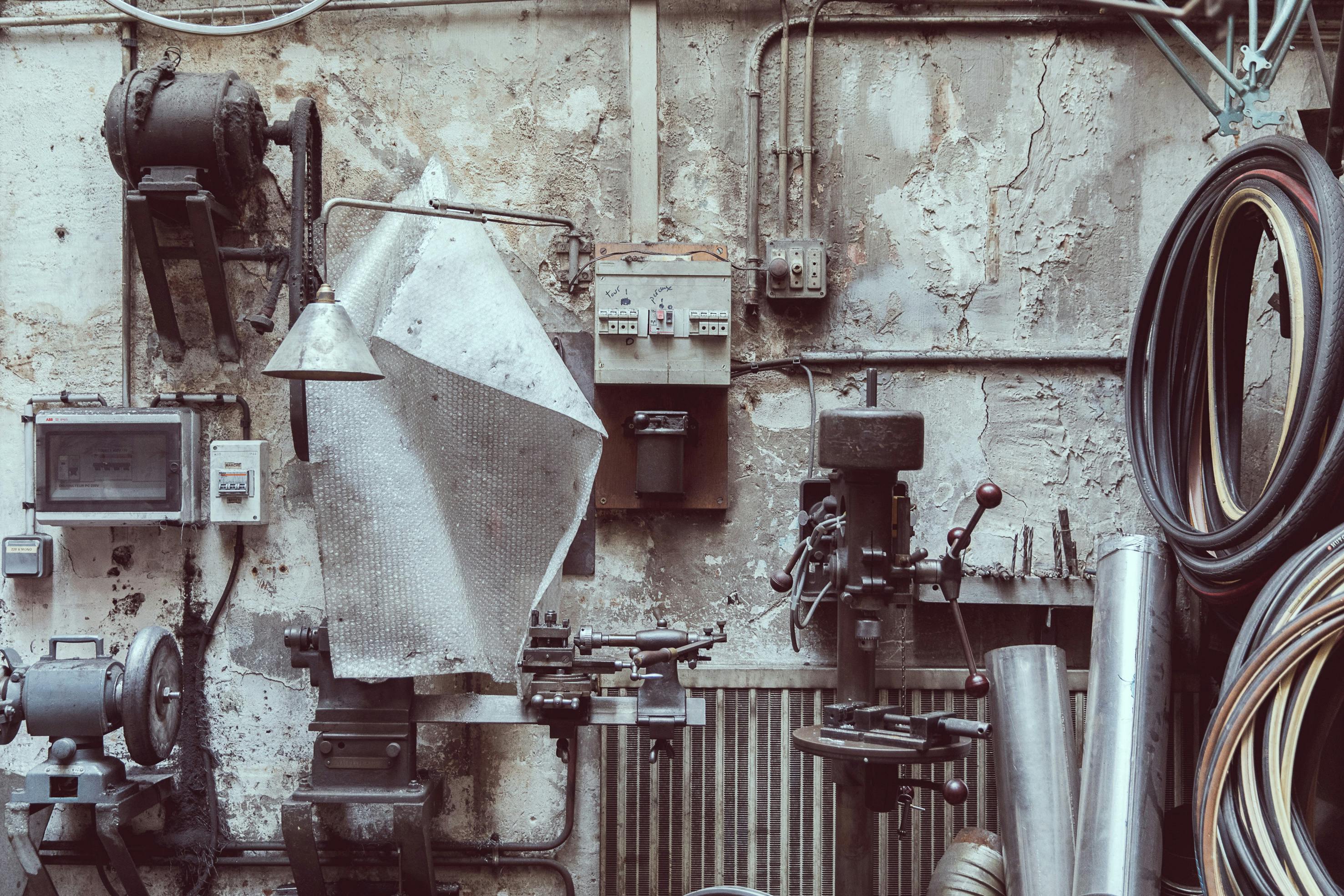

Moving into the back of the building however, the atmosphere changes. Arriving in the workshop is simultaneously stepping back in time and making the most exciting bike discovery of your life, an untouched trove of cycling possibilities. Light streams down from skylights in the double height ceiling showing bicycles in all stages of construction hanging absolutely everywhere: wheels, frames, bikes awaiting repair, ready to be collected or shipped across the world.

It is in this space that Czuka comes alive. He is animated, excited, asking what we want to see, pulling down bikes from the racks to tell the stories behind them, breaking off to answer questions or to adjust a repair that the young mechanic who has returned from lunch is working on.

“This is the bike I had when I was ten,“ says Czuka, showing us an Alex Singer-badged, light blue racing bike complete with drop bars, the saddle of which barely comes above his knee. “I rode up the Galibier on it.” He lets that sink in: one of the most famous climbs in the Alps, hors-categorie that has featured in 34 Tour de France’s, at the age of ten.

Grabbing another bike he tells how he first rode in the Pyrenees after a family friend passed by the shop saying they were heading to the mountains on holiday. Apparently the next thing the young Olivier knew he was pedalling along behind the car. Yet another bike comes with the story of his parents driving him to Liege, just across the French-Belgian border, the bike taken down off the car and a teenage Olivier sent off to ride the course of the brutal one-day classic Liege-Bastogne-Liege. Asking how he got on comes with another shrug: “You can’t stop when you get to Bastogne – the car is still in Liege.” It is clear that, from an early age, the legends of cycling were being instilled in him through riding.

The living heritage tag is completely apt for Alex Singer Cycles. It is a living museum – not only a family legacy of love for the sport, but also to the craft that three generations mastered and quietly championed. Currently being worked on in the shop is a repair, the bike sent back from London to be fixed where it was created, and a new frame build for an Australian customer living in Berlin. The Singer brand is known around the world in specialist steel circles. It has a particularly big fan base in Japan: Czuka shows us a big illustrated coffee table book in Hiragana script dedicated to the brand and he tells us of the invitations he receives from enthusiasts to visit. A photo hangs in the shop of a Japanese couple on their wedding day stood side by side with their Alex Singer bicycles. “They aren’t together any more,” Czuka says, “The only thing that remains constant for him is the bike!”

This is the feeling that you get at Alex Singer Cycles: these frames are a life-long love affair for all involved, customers and creator.

Hanging in the workshop are five frames wrapped in brown paper; written clearly on one is ‘Pinto’. What happened to Pinto, I ask. “He never came to collect his bike,” is the simple answer.

Have you not thought to build up the frame and sell it to somebody else? Czuka looks like I’ve suggested the most ridiculous notion in the world.

“Why would I do that? It would not fit whoever bought it. Even if they had the same dimensions – height, leg length, etc. – their riding style would not be the same. It just wouldn’t work,” he says with a wave of a hand.

The commitment to creating the perfect bicycle for the individual rider is what sets Alex Singer Cycles apart. The determination that this is the correct way, the only way, to go about manufacturing bicycles is what has ensured the endurance of the shop. Sat amongst a seemingly hopeless jumble of tools is the original jig that Alex Singer used to build frames, and what Olivier Czuka continues to use. Pinned on the wall is piece of paper with three frames hand drawn, complete with full measurements. There is no computer mapping here, it isn’t necessary if you know exactly what you are doing. Sat on top of the tools is the jewel of this treasure trove: a frame, uncoated steel, the welding recently finished, and Czuka taps it and lets the clear note ring through the workshop like a tuning fork has been struck, demonstrating that there are no imperfections in the joins.

This is pure passion and skill passed down through a family, a refusal to compromise but keeping cycling at the heart of what they do – beautiful bikes, yes, but beautiful bikes that are made to be ridden, delivering the utter joy of riding a perfect bicycle made just for you.