Subida À Glória

With an average incline of 17% over 265 metres of cobblestones and tramtracks, the Subida à Glória, or Climb to Glory, certainly lives up to its billing. The current record holder is Ricardo Marinheiro with a time of 35.59 seconds, enough to earn him the nickname ‘The Torpedo’, which also sounds fitting.

Text: Jethro Soutar

Photos: Archive -Volta a Portugal

The Subida à Glória is Portugal’s most prestigious hill race. Held at night in the heart of Lisbon, it is also its most popular with spectators packing the narrow pavements and creating a party atmosphere.

“The crowd really spurs you on when you’re out of breath and energy,” says Marta Branco, winner of the women’s race in 2017 and 2018. “It’s a great atmosphere, but what really makes the race so special is the incline!”

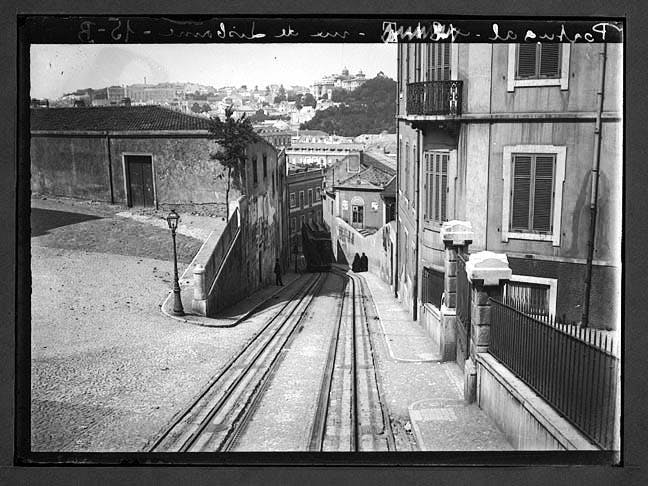

Indeed: Lisbon is a hilly city, but this one is a brute. The race heads up the Calçada da Glória, which literally connects downtown (Baixa) to uptown (Bairro Alto) and pushes 28% at its steepest section. The street has been served by a funicular since 1885, though it’s mostly tourists who enjoy the two-minute ride these days.

Thus the race takes its name from the street, which was in turn named after the Our Lady of Glory chapel it once led to. (Our Lady of Glory is as an alternative to Our Lady of the Assumption in Portuguese.) The chapel was destroyed in the 1755 earthquake and later rebuilt across town, but the street kept its name.

The Subida à Glória begins as a time trial and ends as a head-to-head. Riders first set off at one minute intervals from a ramp attached to the funicular carriage at the bottom of the hill. The four fastest male and female riders qualify for semi-finals and race off side-by-side (fastest versus fourth; second versus third), with the winners of each heat qualifying for the final.

The race against the clock is an explosive affair. “Every millisecond counts, rest doesn’t even enter the vocabulary,” says Marta. “Attempt any kind of race management and you’ll lose out to riders going flat out.”

For the head-to-head races, tactics do come into play and a coin is tossed to decide which side of the carriage riders start from. This is important, but not decisive: the inside lane makes for a tighter racing line as the road takes a dog leg left before correcting into a finishing straight, but the tram tracks still have to be negotiated; there isn’t room to ride in the curb due to the number of spectators and because two funiculars operate in tandem, each employing three rails, the road becomes a convergence of tracks at the bend.

“The key thing you’ve got to be aware of is the carriage tracks,” says Marta. “Being a millimetre out with your racing line can be the difference between winning it and losing it, or a good time and a very bad one because if you make a mess of crossing the tracks, given the incline, you can come to a complete stop.”

As a spectator, seeing whether riders wipe out as they tackle the rails on the bend is a thrilling if guilty pleasure. I got the impression that any rider going for the record simply pretended the tracks weren’t there: that in order to break the record you had to skate straight over them and get lucky.

There’s more to it than that, of course, and riders such as Marta are much more calculating. For a start, there are bike choices to be made.

“It comes down to personal taste, but mountain bikes undoubtedly have the advantage over road bikes when crossing the tracks because of their wider tyres. Some riders use a mountain bike but with adjustments to make it more aerodynamic and rigid, to make sure all the force you exert is applied to the max. That’s certainly my approach, but I’m more comfortable on a mountain bike anyway as I spend most of the season riding one.”

Indeed though a road race, the Subida à Glória seems to favour mountain bike specialists. Marta is a national XCO champion as is Marinheiro, who competes on the UCI World Cup circuit.

Marinheiro won the Subida à Glória in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2017, establishing the current race record in 2015. In fact he set a new record the first three times he won the race, which in 2013 meant breaking a record that had stood for 87 years.

Cyclists first raced up the Calçada da Glória in 1910, José Moura doing so quickest in a time of 1 minute and 23 seconds. Three years later the race gained official status and by 1926 news footage shows throngs of behatted men and women lining the slope six deep to see Alfredo Luís Piedade set a new record of 55 seconds. But a military coup later that year ushered in a dictatorship that would last until 1974. Crowds in public places, indeed fun in general, was off the agenda.

The race was consigned to the history books, but in 2013 a group of enthusiasts persuaded the cycling federation to relaunch the event. One hundred years after the first official meet, the centenary race took place, but the cycling Gods were in a wicked mood and the heavens opened. Besides the gradient and tram tracks, the riders now had wet cobbles and oil grease washed off the rails to contend with. Simply getting up the hill was a challenge and the curve became a banana skin.

But despite the rain, the race proved popular. Jogos Santa Casa, Portugal’s national lottery, took over sponsorship and the event has become something of an annual jamboree. Open to all-comers – though limited to 300 places – the race attracts a mixture of professionals, amateurs, celebrities and jokers, much in the manner of a marathon. A number of former pros tackle the ascent in vintage cycling gear – Marco Chagas, a four-time Tour of Portugal winner in the 1980s, is a regular – while others do so wearing fancy dress or riding folding bikes or food delivery trikes, with a prize awarded for the “Most Original” rider to make it to the top.

At the more serious end, professionals must ride a bike weighing at least 6,800 grammes and featuring a minimum of one brake to qualify for the record.

“Every rider who wants to win the race is always going for the record,” says Marta. “It’s going to be very hard because the time Ricardo Marinheiro set is impressive, but we came close last year, Miguel Salgueiro, who won the men’s race, was just a second off.”

Marta is more aware than most of just how close Miguel got to the record, for he’s her other half. “Last year was extra special because I won the women’s race and my boyfriend won the men’s race, something I’ll remember for the rest of my life,” she says. “But I’ve won it twice now so it’s always going to be a special race for me. I’ll take part whenever and for as long as I can!”