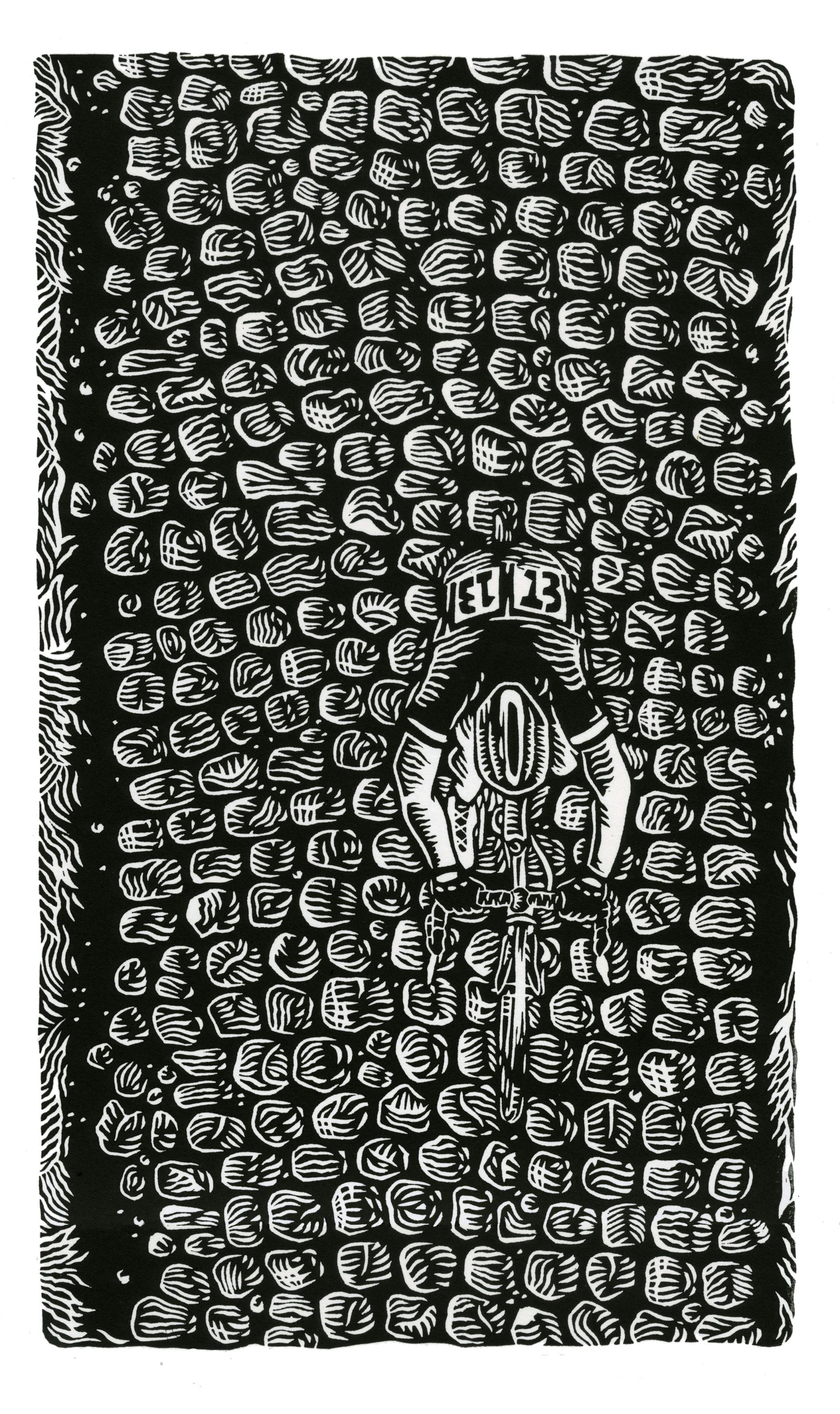

The Hell of The North

Known as the Queen of the Classics, the Hell of the North and a Sunday in Hell, the Paris-Roubaix is arguably the toughest one-day race in the world. First held in 1896, the gruelling course takes riders more than 250 kilometres north of the French capital through narrow cobblestoned farm tracks that are notoriously painful and exhausting.

Text: Pete Dawson

Illustration: Sue Van Gageldonk

Over the years, the pavé or cobbles have caused countless punctures, broken derailleurs, buckled wheels and catastrophic crashes. It’s fitting then, that the winner’s trophy is not a shiny golden cup or a glistening glass statue, but a worn granite cobblestone from the course mounted on a wooden plinth. These iconic cobbles have become an enduring symbol of cycling’s greatest virtues: grit, determination and a stoic endurance of suffering.

The Hell of the North is unlike any other race in modern cycling, even standing out among the other monument classics. The unpredictable cobbled sections require riders to expend significantly more energy to maintain speed while constantly adjusting their position on the bike and never establishing a rhythm. When its dry, riders are engulfed in a choking cloud of dust and when its wet, the cobbles become treacherously slippery. Despite this, riders maintain average speeds in excess of 40km/h and complete the course in under six hours. While most races begin at a relaxed pace and spare the team leaders for later, the big names of the Paris-Roubaix are in the fight much earlier. The race concludes with a ferociously contested sprint around the Roubaix Velodrome in front of a fanatical crowd.

Deep in the Arenberg forest, about halfway through the course, lies a 2.4-kilometre stretch of bone-rattling madness ominously named ‘La Tranchée’ or ‘The Trench’. It was here in 1998 that Johan Museeuw, three-time winner of both the Tour of Flanders and the Paris–Roubaix, crashed and shattered his kneecap. In 2001, Philippe Gaumont was leading the race when he came unstuck in The Trench and snapped his femur. Riders can thank French champion Jean Stablinski for dreaming up this nightmarish section after he was asked by course designers in 1967 to locate some new cobbled roads. Stablinski cautiously suggested the Trench, having worked in the nearby mine years before, but he wasn’t sure if it could even be ridden.

These foreboding roads probably wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for a dedicated group of race enthusiasts nicknamed the ‘forçats du pavé’ or ‘convicts of the cobbles’. Every winter, the volunteers tirelessly re-pave any damaged sections of the course and restore the centuriesold pavé to their former glory. Prior to the 1950s, cobbles were part and parcel of professional road racing, but as private vehicles became more popular they were gradually replaced by smoother asphalt roads. By 1965, only 22 kilometres of cobbled roads remained in the entire Paris-Roubaix course. Thankfully, the cobbles are now seen as an irreplaceable part of France’s heritage, having tested some of the greatest names in cycling including Eddy Merckx, Roger De Vlaeminck, Fabian Cancellara, Francesco Moser and Tom Boonen.

Traditionally, riders who have completed the race gather under the rickety old showers of the Roubaix Velodrome, caked in mud and blood, to compare battle scars and recount tales of valour. After winning the race in 1981, Bernard ‘The Badger’ Hinault famously said “Paris-Roubaix est une connerie” or “Paris–Roubaix is bullsh*t”. Four years later, Dutch rider Theo de Rooij was forced to abandon the race after a crash in The Trench and exclaimed “It’s bollocks, this race! You’re working like an animal, you don’t have time to piss, you wet your pants. You’re riding in mud like this, you’re slipping around, it’s a piece of sh*t”. Moments later, when asked if he would ever return, de Rooij replied “Sure, it’s the most beautiful race in the world”.