A Different Kind of Storytelling

Covering his 30th Tour de France next year, American photographer James Startt continues to admire the beauty of cycling. We met up with him in his apartment in Paris, talking about the importance of storytelling and how he ended up shooting Lance Armstrong’s cancer shots for his biography.

Text: Mari Oshaug

Photos: James Startt & Mari Oshaug

I guess I’m known as the cycling guy because I’ve spent 25 years doing this. But I think I got into photography a bit differently than others – I went to art school and got a masters in Art History. I thought I was going to be a teacher, but then I decided to focus on photography and thought maybe I’ll teach fine art photography.

At the same time, I was also racing bikes as a passion. I started out by running at Indiana University, but I found myself getting injured a lot, so I had to find another sport. I decided to start cycling because it was similar to running. Indiana is a very big center for cycling in the United States, so that’s how I got into bicycle racing. I would go to criterium races and bring my camera, so between my races I would shoot others. I didn’t know at the time that this was the start of what would later become my career.

My wife studied French at the time, and I got a job opportunity in Paris, which allowed me to come along and race. We later decided to move to Paris and I suddenly had to look for more creative ways of work. Paris is known for being a center of art and cycling, so it suited me well. But in Europe everybody wants to be a photographer. I was out on a bike ride one day and I thought, I do have a niche here. I enjoy cycling, I know the sport well, why not combine the two? So, I started sending out pictures and after a couple of years it eventually became my living.

At the same time – since I came from a fine arts background – my first love was street art photography. I wrote my masters on William Klein (born April 19, 1928) an American-born French photographer and filmmaker noted for his ironic approach to both media and his extensive use of unusual photographic techniques in the context of photojournalism and fashion photography.

I always did sport photography like it was street photography. I never took a photo journalism class, which would have thought me the classic ways of storytelling, so it took me about 20 years to figure that out.

I shot my first Tour de France with a little pocket Olympus XA 28 mm and everybody looked at me like I was a Martian. It took me years to get over that first experience, because no one took me seriously. As a cycling photographer at the Tour, if you don’t have a 200 or 400mm bazooka lens then you’re not serious about it. But that was the first camera I used at the Tour de France.

I continued to do both street art and sport photography. In the 1990s I started working with the oldest photo gallery in Paris, Galerie Agathe Gaillard, where I’ve had several exhibitions. My first one was on cycling, then I did two on street art, as well as jazz music, which is also a huge part of my life.

To add to that, Agathe Gaillard founded the gallery in 1975 in the Marais, a central district in the city. She was encouraged by photographers such as Jean-Philippe Charbonnier, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Andre Kertesz, Édouard Boubat and Robert Doisneau. The gallery is the first in Europe devoted solely to the art of photography with the goal of bringing it into contemporary art as a specific domain.

At first, I said that my cycling photography is just commercial stuff. But I’ve never been able to keep straight lines when it comes to my work. I have to combine my passions with my professional work. It was with the cycling photography that I realised I could make a living out by combining riding and shooting. Actually, some of my strongest pictures are of cycling.

One my first series on cycling photography was after the finish line. For years I traveled around and didn’t really care about the race that much; I was just trying to get to the finish line. This work was very inspired by William Klein – close and emotional.

Around 2008 I started collaborating with a photo agency here in France called Zoom. We started developing cycling as a summer sport and they pushed me to be broader in my picture taking. I still do after the finish line stuff, but it’s great to have someone push you creatively in a new direction. I have to have the landscape scenery and I have to have the stock finish line. But also combined with other commercial stuff and portraits, it been a great creative push and pull.

Last summer I picked up this old half frame Olympus camera from the 60s. This camera takes 72 pictures for each role of film. If you look through the lens you’ll see that it’s vertical, so it puts two vertical frames in the space of what is generally one negative. This is really interesting because you sometimes get these weird parings in terms of positioning and also because the negatives are so small, they compensated with really great lenses.

This again made me sense a more nostalgic way of picture taking when I’m out traveling the landscapes of France. So, during the Tour in 2017 I started early by driving ahead of the race and made stops around the villages to shoot the details of the town and the people without the cyclists. The colours are amazing and it has this retro feel to it. It is a different kind of storytelling. I’m never quite sure what I’m going to get, but it always comes with great surprises.

I started shooting with film again lately, but it quickly reminded me of how expensive it is and how you’re back to getting only a few nice pictures per role. You become much more aware of your failures because you can’t just go back and delete them. But when they work, they really work, and there is something great about that which you can’t compare to digital. I sold one of my frames to a collector and I was so worried about how they would blow up, but that’s the beauty of film, they scale so well because you’re working with grain, not pixels. I obviously could never shoot the races with film because it’s too slow for that, but for the right situation nothing beats film.

BV: How do you approach photography to tell the best story?

JS: It really depends on the type of picture taking I’m doing. Anytime I’m doing a story I’m constantly thinking in a reportage sense – a beginning, middle and end. Being at the back of a motorbike at a race, that narratives is assigned to you. There is a beginning, a middle, a break away, a chase and a finish. But I always try to tell the story in own my way by using a variety of tools, such as choices of lenses and angles. This reflects the things I learned from street photography. Unlike some “classic” sports photographers, I’m not just about the hype of action. I try to put each race in its context, showing the fans, the scenery and the villages we pass. With my photos, you’ll know you are in Argentina, not Japan. I focus on the important moments that help telling the whole story.

Other times as a sports photographer I’m assigned to document more aspects of behind the scenes. The main part of my work, besides the “after the finish line”, is doing behind the scenes. When I work on commercial stuff for brands like Zipp and Gortex, where I follow a rider up an alpine climb, I have to think about getting their bike ready, showing the materials, then the ride and the scenery. It’s a different way of telling a story.

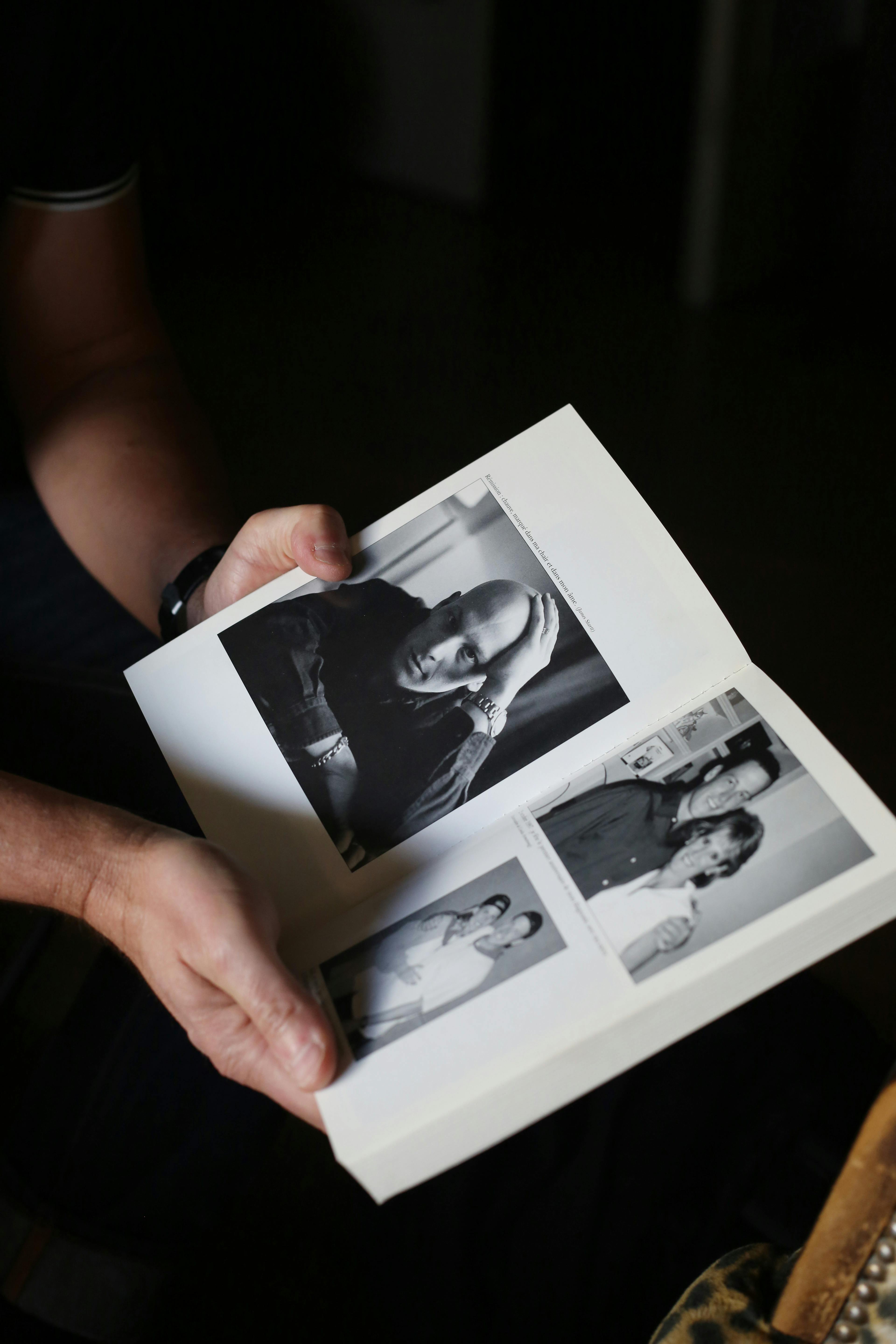

Portrait stories are important, too. I always try to mix in some portraits in my storytelling. When I took Lance Armstrong’s cancer shots for his biography, it was a very different way of telling a story – in a single shot. At the time I was one of the few Americans in Europe covering the sport, so Lance and I had a friendly and pretty close relationship for a while. I went to his house in Italy, and often in races we got together. But the cycling sport was so different back then. No one had busses back then, they all traveled by cars or mini vans, but pretty small and basic, so it made the access to the rider easier as well. Lance called me up one night saying he was in town and we went out for dinner, and it turned out that it was two weeks before he was diagnosed with cancer. So that turned into me following him through the cancer treatment.

I was back home with my family in Indiana for Christmas at the same time that Lance was getting treated. I called him and said I wanted to see him and document the treatment. I told him, “I’ll come to Texas or if you want to meet up here before the chemo, we’ll do that.” I picked him up at Indiana Airport and took him to the hotel. We met up for dinner and I said “Tomorrow before your chemo, I’d like to do some portraits.” He was not too eager about it obviously, but he agreed. I brought my old Mamiya camera with 12 pictures on a role, so I told Lance that it would be a quick session. I pulled up a chair next to a window and got him to relax, but since he was going through chemo, his skin complexion wasn’t great. I decided to shoot it in black and white to make it more appropriate. I think we shot two roles before I sent him off and that was that. So fast forward to the eve of his first Tour victory after the chemo, I called him and expressed that I’d really like to redo the image, like a before and after. That ended up becoming the cover of his book.

When we shot the photos, the purpose was not for the book or anything else. It was based on our relationship and documenting what Lance was going through. He trusted me to do decent work and to treat it with dignity. At the time no one was really shooting portraits of cyclists like that. It was not the priority in the sport. So, it was a pleasant surprise when Nike called me years later and said that they would like to use one of my photos for an ad campaign. Apparently, they turned out to be some of Lance’s favourite photos.

Ultimately, I try to have dignity in all the work that I do. Even at the worst of the times, with the doping scandals, I still had pretty good access because the teams knew that I cared about the beauty of the sport more than anything else.

I was certainly bothered by the doping; how can you not be. When Lance started winning the Tour de France all of a sudden, the way he was doing it raised some questions for me. I knew Lance long before he started winning, and although I had no proof of doping, I was suspicious. I’ve been in the sport for a long time and having lived through the Festina scandal the year before (1998), it all seemed a bit too close for comfort. But I do believe you are innocent until you’re proven guilty, so it’s not for me to say if someone’s guilty or not, based on suspicion.

On that note, I never used the word doping in any of my writing, but I did start to pick and choose my adjectives. I stop using words like miraculous and replaced it with impressive or overwhelming. The years after the doping scandal I was never as close with Lance and by the time he fell, it just had to happen. I chose to step back for it all. At the time I was working with the magazine Bicycling and I was very happy that they didn’t pressure me to go after the Lance story. Some of my friends had to have Lance in every paragraph, even if he had finished 131st, that had to be the front line of the story, just because it was Lance.

I try to have a good professional working relationship, but it’s harder to get access once the machinery around a rider starts working. You never really get anything exclusive, so it better to step back and look at them from a far, like I did with Lance.

I’ve always preferred to do the smaller stories, on the mechanics, the drivers, the guys around the scene, rather than the stars and the champion. Although the race is centered around winning, the beauty of everything surrounding the sport is much more interesting. The Festina and Armstrong affair brought in a whole new school of investigating journalism. I had to make a choice to do my job because I love the sport and still find it fascinating after all these years. If I was going to be an investigative reporter, I would end up closing a lot of doors with friends and people I respect, and that has never been for me.

BV: You covered you’re first Tour in the 1990. How was the scene then compared to today?

JS: It has always been a huge show. I remember the first interview I did with Jean-Marie Leblanc (a French retired professional road cyclist who was General Director of the Tour de France from 1989 to 2005). He told me to watch out for the “la géante”, the giant size of the Tour. I didn’t know what he meant by that, I was just thinking how can it get any bigger? But looking back at it now, it certainly was smaller.

Cycling was so much more closed before. You were in or out. It was an insiders game. You had to be part of the inner circle, and if you weren’t, they didn’t care at all. Where today it is much more open.

In terms of photo journalism, there’s a huge difference. When I first showed up in the 90s, you didn’t mix writing and photography. I’ve been in physical fights with some of the photographers. They did not want me at the finish line. They told me, “You’re doing the interviews and write the stories on these guys. You don’t have the right to take pictures like we do.” I got upset because at the time I didn’t have the money to support a motorbike, like the other photographers did. I had to take what I could get.

My clients at the time were interested in the words and the stories I could get, and my photography was illustrating the stories. But that all changed with the internet. Today I get pressured into doing video on top of it all. I was one of the first guys mixing it up, but I’m not interested in doing video. I’m sure there will be a young kid with all the tools that can do it all in a second, but that is not the thing for me.

BV: It seems like the aspect you care about the most has always been the story?

JS: Oh yeah. I have the shittiest equipment out there. Most of my camera bodies and lenses are used, but I like that. I like the flaws and imperfections of photography. No one else would show up to the Tour with a 12mm lens. Back in the days I could have done the entirety of the three weeks of the Tour with just that.

Additionally, I don’t like equipment that is too limiting. I like to be able to move around and if your too weighted down you can’t run that fast, although I’m getting slower by the years.

In terms of storytelling it’s important to have access to people. After 25 years I have a lot of contacts. That helps.

BV: Which cyclists have had the most impact on you?

JS: That is a good question. My first response is probably Lance. I had dinner with him in Toulouse the first year he went pro and followed his entire carrier from there. I visited him two times in Berlin, and we did the book, photo journals and race diaries together for five years of the Tour. One of my favourite pictures is of him. He is really just one of the few riders that actually did become a friend.

In terms of the older generation, I’ve met Eddy Merckx, and I’ve been in the same room as Gino Bartali in Italy in the 90s, and Roger Walkowiak (1927-2017) as well. I met Roger right before he died at his home in Vinchy in the center of France. I got him to take out his jerseys and told me about his victory at the 1956 Tour de France. The oldest rider has to be Robert Marchand (1911).

BV: I find it interesting to talk about the older generation and keeping the stories alive. I guess that’s what you’re doing with photography as well?

JS: Yes. I like talking to the old guys, too. In one story I went back to the old ACBB club, which was an amateur club outside of Paris who brought in the first Anglo-Saxon riders. Robert Millar, Stephen Roche and Philip Grant Anderson all became pros here. Amazing story.

BV: Do you have a favourite client that you been working with?

JS: Creatively, Peloton Magazine has been outstanding. I’ve never had better creative editors. I’ve had pictures published in Vanity Fair and The New York Times, but I don’t have a working relationship with them, as I have with Peloton. It’s finally a magazine that is the perfect fit for me, in terms of the balance between writing and photography, great editors, great design… and they listen to me, which I appreciate. I’ve been more creative than I ever was with Peloton.

BV: Do you still do street photography when you’re out and about?

JS: Yes, I have four cameras in my little bag of tricks. I got a half frame, a digital, an old Panoramic camera and a little Sony RX100 pocket camera. I always have one or more cameras with me. Several of the pictures that are at the Galerie Agathe Gaillard right now are shot on my little Sony. When I’m out on the street I don’t think about bikes or looking for anything in particular. It can be a staircase. Yesterday it was an escalator that I thought was pretty cool. I shoot anything that interests me. Whatever tells the story.

BV: How do you see your future as a photographer?

JS: I don’t know. There is a lot of movement, traditional journalism is constantly redefining itself, and for as long as I’ve been a photographer I’ve heard how the written press is dying and has no future. And yet it is still here. You see it in independent magazines, and with vinyl records and film cameras, too. There is a desire and a need to go back to the roots of things in order to get the real quality. No matter what the future brings, there will always be room for great storytelling.